1. Why was Sisyphus condemned to roll his rock?

2. What did Homer say Sisyphus had conquered?

3. Why must we imagine Sisyphus happy, according to Camus?

3. Why must we imagine Sisyphus happy, according to Camus?

DQ:

1. Is anything worse, in your experience, than futile, hopeless labor?

2. What could it mean for a mortal to put Death in chains?

3. Must we imagine Sisyphus happy?

3. Must we imagine Sisyphus happy?

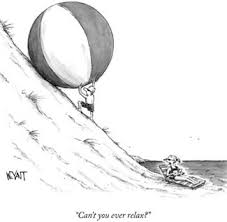

The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.

If one believes Homer, Sisyphus was the wisest and most prudent of mortals. According to another tradition, however, he was disposed to practice the profession of highwayman. I see no contradiction in this. Opinions differ as to the reasons why he became the futile laborer of the underworld. To begin with, he is accused of a certain levity in regard to the gods. He stole their secrets. Egina, the daughter of Esopus, was carried off by Jupiter. The father was shocked by that disappearance and complained to Sisyphus. He, who knew of the abduction, offered to tell about it on condition that Esopus would give water to the citadel of Corinth. To the celestial thunderbolts he preferred the benediction of water. He was punished for this in the underworld. Homer tells us also that Sisyphus had put Death in chains. Pluto could not endure the sight of his deserted, silent empire. He dispatched the god of war, who liberated Death from the hands of her conqueror.

It is said that Sisyphus, being near to death, rashly wanted to test his wife's love. He ordered her to cast his unburied body into the middle of the public square. Sisyphus woke up in the underworld. And there, annoyed by an obedience so contrary to human love, he obtained from Pluto permission to return to earth in order to chastise his wife. But when he had seen again the face of this world, enjoyed water and sun, warm stones and the sea, he no longer wanted to go back to the infernal darkness. Recalls, signs of anger, warnings were of no avail. Many years more he lived facing the curve of the gulf, the sparkling sea, and the smiles of earth. A decree of the gods was necessary. Mercury came and seized the impudent man by the collar and, snatching him from his joys, lead him forcibly back to the underworld, where his rock was ready for him.

You have already grasped that Sisyphus is the absurd hero. He is, as much through his passions as through his torture. His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing. This is the price that must be paid for the passions of this earth. [Compare the exhaustion of Nietzsche's mountain climber] Nothing is told us about Sisyphus in the underworld. Myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them. As for this myth, one sees merely the whole effort of a body straining to raise the huge stone, to roll it, and push it up a slope a hundred times over; one sees the face screwed up, the cheek tight against the stone, the shoulder bracing the clay-covered mass, the foot wedging it, the fresh start with arms outstretched, the wholly human security of two earth-clotted hands. At the very end of his long effort measured by skyless space and time without depth, [compare time as "the greatest weight"] the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward that lower world whence he will have to push it up again toward the summit. He goes back down to the plain. [Like Zarathustra?]

It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock. [compare Bertrand Russell, "A Free Man's Worship" - "The life of man is a long march..."]

If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works everyday in his life at the same tasks, and his fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that can not be surmounted by scorn.

If the descent is thus sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy. This word is not too much. Again I fancy Sisyphus returning toward his rock, and the sorrow was in the beginning. When the images of earth cling too tightly to memory, when the call of happiness becomes too insistent, it happens that melancholy arises in man's heart: this is the rock's victory, this is the rock itself. The boundless grief is too heavy to bear. These are our nights of Gethsemane. But crushing truths perish from being acknowledged. Thus, Edipus at the outset obeys fate without knowing it. But from the moment he knows, his tragedy begins. Yet at the same moment, blind and desperate, he realizes that the only bond linking him to the world is the cool hand of a girl. Then a tremendous remark rings out: "Despite so many ordeals, my advanced age and the nobility of my soul make me conclude that all is well." Sophocles' Edipus, like Dostoevsky's Kirilov, thus gives the recipe for the absurd victory. Ancient wisdom confirms modern heroism.

One does not discover the absurd without being tempted to write a manual of happiness. "What!---by such narrow ways--?" There is but one world, however. Happiness and the absurd are two sons of the same earth. They are inseparable. It would be a mistake to say that happiness necessarily springs from the absurd. discovery. It happens as well that the felling of the absurd springs from happiness. "I conclude that all is well," says Edipus, and that remark is sacred. It echoes in the wild and limited universe of man. It teaches that all is not, has not been, exhausted. It drives out of this world a god who had come into it with dissatisfaction and a preference for futile suffering. It makes of fate a human matter, which must be settled among men.

All Sisyphus' silent joy is contained therein. His fate belongs to him. His rock is a thing Likewise, the absurd man, when he contemplates his torment, silences all the idols. In the universe suddenly restored to its silence, the myriad wondering little voices of the earth rise up. Unconscious, secret calls, invitations from all the faces, they are the necessary reverse and price of victory. There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night. The absurd man says yes and his efforts will henceforth be unceasing. If there is a personal fate, there is no higher destiny, or at least there is, but one which he concludes is inevitable and despicable. For the rest, he knows himself to be the master of his days. At that subtle moment when man glances backward over his life, Sisyphus returning toward his rock, in that slight pivoting he contemplates that series of unrelated actions which become his fate, created by him, combined under his memory's eye and soon sealed by his death. Thus, convinced of the wholly human origin of all that is human, a blind man eager to see who knows that the night has no end, he is still on the go. The rock is still rolling.

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one's burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

---Albert Camus

If one believes Homer, Sisyphus was the wisest and most prudent of mortals. According to another tradition, however, he was disposed to practice the profession of highwayman. I see no contradiction in this. Opinions differ as to the reasons why he became the futile laborer of the underworld. To begin with, he is accused of a certain levity in regard to the gods. He stole their secrets. Egina, the daughter of Esopus, was carried off by Jupiter. The father was shocked by that disappearance and complained to Sisyphus. He, who knew of the abduction, offered to tell about it on condition that Esopus would give water to the citadel of Corinth. To the celestial thunderbolts he preferred the benediction of water. He was punished for this in the underworld. Homer tells us also that Sisyphus had put Death in chains. Pluto could not endure the sight of his deserted, silent empire. He dispatched the god of war, who liberated Death from the hands of her conqueror.

It is said that Sisyphus, being near to death, rashly wanted to test his wife's love. He ordered her to cast his unburied body into the middle of the public square. Sisyphus woke up in the underworld. And there, annoyed by an obedience so contrary to human love, he obtained from Pluto permission to return to earth in order to chastise his wife. But when he had seen again the face of this world, enjoyed water and sun, warm stones and the sea, he no longer wanted to go back to the infernal darkness. Recalls, signs of anger, warnings were of no avail. Many years more he lived facing the curve of the gulf, the sparkling sea, and the smiles of earth. A decree of the gods was necessary. Mercury came and seized the impudent man by the collar and, snatching him from his joys, lead him forcibly back to the underworld, where his rock was ready for him.

You have already grasped that Sisyphus is the absurd hero. He is, as much through his passions as through his torture. His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing. This is the price that must be paid for the passions of this earth. [Compare the exhaustion of Nietzsche's mountain climber] Nothing is told us about Sisyphus in the underworld. Myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them. As for this myth, one sees merely the whole effort of a body straining to raise the huge stone, to roll it, and push it up a slope a hundred times over; one sees the face screwed up, the cheek tight against the stone, the shoulder bracing the clay-covered mass, the foot wedging it, the fresh start with arms outstretched, the wholly human security of two earth-clotted hands. At the very end of his long effort measured by skyless space and time without depth, [compare time as "the greatest weight"] the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward that lower world whence he will have to push it up again toward the summit. He goes back down to the plain. [Like Zarathustra?]

It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock. [compare Bertrand Russell, "A Free Man's Worship" - "The life of man is a long march..."]

If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works everyday in his life at the same tasks, and his fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that can not be surmounted by scorn.

If the descent is thus sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy. This word is not too much. Again I fancy Sisyphus returning toward his rock, and the sorrow was in the beginning. When the images of earth cling too tightly to memory, when the call of happiness becomes too insistent, it happens that melancholy arises in man's heart: this is the rock's victory, this is the rock itself. The boundless grief is too heavy to bear. These are our nights of Gethsemane. But crushing truths perish from being acknowledged. Thus, Edipus at the outset obeys fate without knowing it. But from the moment he knows, his tragedy begins. Yet at the same moment, blind and desperate, he realizes that the only bond linking him to the world is the cool hand of a girl. Then a tremendous remark rings out: "Despite so many ordeals, my advanced age and the nobility of my soul make me conclude that all is well." Sophocles' Edipus, like Dostoevsky's Kirilov, thus gives the recipe for the absurd victory. Ancient wisdom confirms modern heroism.

One does not discover the absurd without being tempted to write a manual of happiness. "What!---by such narrow ways--?" There is but one world, however. Happiness and the absurd are two sons of the same earth. They are inseparable. It would be a mistake to say that happiness necessarily springs from the absurd. discovery. It happens as well that the felling of the absurd springs from happiness. "I conclude that all is well," says Edipus, and that remark is sacred. It echoes in the wild and limited universe of man. It teaches that all is not, has not been, exhausted. It drives out of this world a god who had come into it with dissatisfaction and a preference for futile suffering. It makes of fate a human matter, which must be settled among men.

All Sisyphus' silent joy is contained therein. His fate belongs to him. His rock is a thing Likewise, the absurd man, when he contemplates his torment, silences all the idols. In the universe suddenly restored to its silence, the myriad wondering little voices of the earth rise up. Unconscious, secret calls, invitations from all the faces, they are the necessary reverse and price of victory. There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night. The absurd man says yes and his efforts will henceforth be unceasing. If there is a personal fate, there is no higher destiny, or at least there is, but one which he concludes is inevitable and despicable. For the rest, he knows himself to be the master of his days. At that subtle moment when man glances backward over his life, Sisyphus returning toward his rock, in that slight pivoting he contemplates that series of unrelated actions which become his fate, created by him, combined under his memory's eye and soon sealed by his death. Thus, convinced of the wholly human origin of all that is human, a blind man eager to see who knows that the night has no end, he is still on the go. The rock is still rolling.

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one's burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

---Albert Camus

The Myth of Sisyphus and other essays

Let's go, Dodgers...

Let's go, Dodgers...

Podcast-Brave new world... Camus's Myth of Sisyphus... Sisyphus @dawn-BNW, Peace... Sisyphus on "On Being," with an excerpt from Jennifer Michael Hecht's Stay - Chapter 8, "Two Major Voices on Suicide"

==

NOV 2 -

A Philosophy of Walking, 1-3

1. What has introduced an invasive "sporting spirit" to the child's play of walking?

2. What does Gros say we escape from, by walking?

3. Nietzsche said you should disbelieve any idea that _____.

4. Where and how did Nietzsche write The Wanderer and His Shadow? *

5. How did Nietzsche's walks differ from Kant's?

6. What advantage does the peripatetic author have over his desk-bound counterpart?

7. Nietzsche preferred climbing because it affords a _____ outlook.

8. What Nietzschean idea does Gros explicitly connect to the experience of walking, particularly long repeated excursions on familiar paths?

9. For Nietzsche the discovery of Turin brought a renewal of _____.

DQ

Why people walk is a hard question that looks easy. Upright bipedalism seems such an obvious advantage from the viewpoint of those already upright that we rarely see its difficulty. In the famous diagram, Darwinian man unfolds himself from frightened crouch to strong surveyor of the ages, and it looks like a natural ascension: you start out bending over, knuckles dragging, timidly scouring the ground for grubs, then you slowly straighten up until there you are, staring at the skies and counting the stars and thinking up gods to rule them. But the advantages of walking have actually been tricky to calculate. One guess among the evolutionary biologists has been that a significant advantage may simply be that walking on two legs frees up your hands to throw rocks at what might become your food—or to throw rocks at other bipedal creatures who are throwing rocks at what might become their food. Although walking upright seems to have preceded throwing rocks, the rock throwing, the biologists point out, is rarer than the bipedalism alone, which we share with all the birds, including awkward penguins and ostriches, and with angry bears. Meanwhile, the certainty of human back pain, like the inevitability of labor pains, is evidence of the jury-rigged, best-solution-at-hand nature of evolution.

Over time, though, things we do for a purpose, however obscure in origin, become things we do for pleasure, particularly when we no longer have to do them. As we do them for pleasure, they get attached either to a philosophy or to the pursuit of some profit. Two new accounts of this process have recently appeared, and although they occasionally make you want to throw things, they both illuminate what it means to be a pedestrian in the modern world.

Matthew Algeo’s “Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport” (Chicago Review) is one of those books which open up a forgotten world so fully that at first the reader wonders, just a little, if his leg is being pulled. How could there be an account this elaborate—illustrated with sober handbills, blaring headlines, starchy portrait photographs, and racy newspaper cartoons—of an enthusiasm this unknown? But it all happened. For several decades in the later nineteenth century, the favorite spectator sport in America was watching people walk in circles inside big buildings... (continues)

WHY WALKING HELPS US THINK. By Ferris Jabr

In Vogue’s 1969 Christmas issue, Vladimir Nabokov offered some advice for teaching James Joyce’s “Ulysses”: “Instead of perpetuating the pretentious nonsense of Homeric, chromatic, and visceral chapter headings, instructors should prepare maps of Dublin with Bloom’s and Stephen’s intertwining itineraries clearly traced.” He drew a charming one himself. Several decades later, a Boston College English professor named Joseph Nugent and his colleagues put together an annotated Google map that shadows Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom step by step. The Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain, as well as students at the Georgia Institute of Technology, have similarly reconstructed the paths of the London amblers in “Mrs. Dalloway.”

Such maps clarify how much these novels depend on a curious link between mind and feet. Joyce and Woolf were writers who transformed the quicksilver of consciousness into paper and ink. To accomplish this, they sent characters on walks about town. As Mrs. Dalloway walks, she does not merely perceive the city around her. Rather, she dips in and out of her past, remolding London into a highly textured mental landscape, “making it up, building it round one, tumbling it, creating it every moment afresh.”

Since at least the time of peripatetic Greek philosophers, many other writers have discovered a deep, intuitive connection between walking, thinking, and writing. (In fact, Adam Gopnik wrote about walking in The New Yorker just two weeks ago.) “How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live!” Henry David Thoreau penned in his journal. “Methinks that the moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow.” Thomas DeQuincey has calculated that William Wordsworth—whose poetry is filled with tramps up mountains, through forests, and along public roads—walked as many as a hundred and eighty thousand miles in his lifetime, which comes to an average of six and a half miles a day starting from age five.

What is it about walking, in particular, that makes it so amenable to thinking and writing? The answer begins with changes to our chemistry. When we go for a walk, the heart pumps faster, circulating more blood and oxygen not just to the muscles but to all the organs—including the brain. Many experiments have shown that after or during exercise, even very mild exertion, people perform better on tests of memory and attention. Walking on a regular basis also promotes new connections between brain cells, staves off the usual withering of brain tissue that comes with age, increases the volume of the hippocampus (a brain region crucial for memory), and elevates levels of molecules that both stimulate the growth of new neurons and transmit messages between them... (continues)

We crave only reality

I may have been hasty in detecting deconstructionist tendencies in Frederic Gros's Philosophy of Walking. Overtly at least, he's on the side of immediate experience and reality, against that of the Derridean overtextualizers. Or so it appears, given his sympathetic rendition of Thoreau's famous "rocks in place" declaration of independence from tradition, convention, and cultural inertia. Honest writing must first acknowledge the truth of the writer's own experience. If he cannot tap that well, he has no business writing. "How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live."

==

NOV 2 -

A Philosophy of Walking, 1-3

1. What has introduced an invasive "sporting spirit" to the child's play of walking?

2. What does Gros say we escape from, by walking?

3. Nietzsche said you should disbelieve any idea that _____.

4. Where and how did Nietzsche write The Wanderer and His Shadow? *

5. How did Nietzsche's walks differ from Kant's?

6. What advantage does the peripatetic author have over his desk-bound counterpart?

7. Nietzsche preferred climbing because it affords a _____ outlook.

8. What Nietzschean idea does Gros explicitly connect to the experience of walking, particularly long repeated excursions on familiar paths?

9. For Nietzsche the discovery of Turin brought a renewal of _____.

DQ

- Walking is not a sport, but it once was. "For several decades in the later nineteenth century, the favorite spectator sport in America was watching people walk in circles inside big buildings." * Comments?

- "We do not belong to those who have ideas only among books," said Nietzsche, "it is our habit to think outdoors." Do you find your own indoor thoughts more bookish, your outdoor thoughts more natural and free? Do we need more practice during class, to notice the difference?

- Do you find that a long walk (hike, bikeride, or some other personally-functional equivalent) makes you feel more yourself, or less like a self at all?

- COMMENT:

*“My thoughts’, said the wanderer to his shadow, ‘should show me where I stand, but they should not betray to me where I am going. I love ignorance of the future and do not want to perish of impatience and premature tasting of things promised.”

The Gymnasiums of the Mind

Christopher Orlet wanders down literary paths merrily swinging his arms and pondering the happy connection between philosophy and a good brisk walk.

If there is one idea intellectuals can agree upon it is that the act of ambulation – or as we say in the midwest, walking – often serves as a catalyst to creative contemplation and thought. It is a belief as old as the dust that powders the Acropolis, and no less fine. Followers of the Greek Aristotle were known as peripatetics because they passed their days strolling and mind-wrestling through the groves of the Academe. The Romans’ equally high opinion of walking was summed up pithily in the Latin proverb: “It is solved by walking.” [solvitur ambulando]

Nearly every philosopher-poet worth his salt has voiced similar sentiments. Erasmus recommended a little walk before supper and “after supper do the same.” Thomas Hobbes had an inkwell built into his walking stick to more easily jot down his brainstorms during his rambles. Jean- Jacques Rousseau claimed he could only meditate when walking: “When I stop, I cease to think,” he said. “My mind only works with my legs.” Søren Kierkegaard believed he’d walked himself into his best thoughts. In his brief life Henry David Thoreau walked an estimated 250,000 miles, or ten times the circumference of earth. “I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits,” wrote Thoreau, “unless I spend four hours a day at least – and it is commonly more than that – sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields absolutely free from worldly engagements.” Thoreau’s landlord and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson characterized walking as “gymnastics for the mind.”

In order that he might remain one of the fittest, Charles Darwin planted a 1.5 acre strip of land with hazel, birch, privet, and dogwood, and ordered a wide gravel path built around the edge. Called Sand-walk, this became Darwin’s ‘thinking path’ where he roamed every morning and afternoon with his white fox-terrier. Of Bertrand Russell, long-time friend Miles Malleson has written: “Every morning Bertie would go for an hour’s walk by himself, composing and thinking out his work for that day. He would then come back and write for the rest of the morning, smoothly, easily and without a single correction.”

None of these laggards, however, could touch Friedrich Nietzsche, who held that “all truly great thoughts are conceived by walking.” Rising at dawn, Nietzsche would stalk through the countryside till 11 a.m. Then, after a short break, he would set out on a two-hour hike through the forest to Lake Sils. After lunch he was off again, parasol in hand, returning home at four or five o’clock, to commence the day’s writing.

Not surprisingly, the romantic poets were walkers extraordinaire. William Wordsworth traipsed fourteen or so miles a day through the Lake District, while Coleridge and Shelley were almost equally energetic. According to biographer Leslie Stephen, “The (English) literary movement at the end of the 18th century was…due in great part, if not mainly, to the renewed practice of walking.”

Armed with such insights, one must wonder whether the recent decline in walking hasn’t led to a corresponding decline in thinking. Walking, as both a mode of transportation and a recreational activity, began to fall off noticeably with the rise of the automobile, and took a major nosedive in the 1950s. Fifty plus years of automobile-centric design has reduced the number of sidewalks and pedestrian-friendly spaces to a bare minimum (particularly in the American west). All of the benefits of walking: contemplation, social intercourse, exercise, have been willingly exchanged for the dubious advantages of speed and convenience, although the automobile alone cannot be blamed for the maddening acceleration of everyday life. The modern condition is one of hurry, a perpetual rush hour that leaves little time for meditation. No wonder then that in her history of walking, Rebecca Solnit mused that “modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought, or thoughtfulness,” which seems the antithesis of Wittgenstein’s observation that in the race of philosophy, the prize goes to the slowest.

If we were to compare the quantity and quality of thinkers of the early 20th century with those of today, one cannot help but notice the dearth of Einsteins, William Jameses, Eliots and Pounds, Freuds, Jungs, Keynes, Picassos, Stravinskys, Wittgensteins, Sartres, Deweys, Yeats and Joyces.... Mark Twain... “walking is good to time the movement of the tongue by, and to keep the blood and the brain stirred up and active.” Others have concluded that walking’s two-point rhythm clears the mind for creative study and reflection... And while Einstein may have been a devoted pedestrian (daily hoofing the mile-and-a-half walk between his little frame house at 112 Mercer Street and his office at Princeton’s Fuld Hall), the inability to walk has not much cramped Stephen Hawking’s intellectual style. [But how would we know?!]

...Here, where the average citizen walks a measly 350 yards a day, it is not surprising that half the population is diagnosed as obese or overweight. Despite such obscene girth, I have sat through planning commission meetings and heard civil engineers complain that it would be a waste of money to lay down sidewalks since no one walks anyway. No one thought to ask if perhaps we do not walk because there are no sidewalks. Even today, the typical urban planner continues to regard the pedestrian as “the largest single obstacle to free traffic movement.”

To paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, walking remains for me the best “of all exercises.” Even so, I am full of excuses to stay put. My neighborhood has no sidewalks and it is downright dangerous to stroll the streets at night; if the threat does not come directly from thugs, then from drunken teens in speeding cars. There are certainly no Philosophers’ Walks in my hometown, as there are near the universities of Toronto, Heidelberg, and Kyoto. Nor are there any woods, forests, mountains or glens. “When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and the woods,” said Thoreau. “What would become of us, if we only walked in a garden or a mall?” I suppose I am what becomes of us, Henry.

At noon, if the weather cooperates, I may join a few other nameless office drudges on a stroll through the riverfront park. My noon walk is a brief burst of freedom in an otherwise long, dreary servitude. Though I try to reserve these solitary walks for philosophical ruminations, my subconscious doesn’t always cooperate. Often I find my thoughts to be pedestrian and worrisome in nature. I fret over money problems, or unfinished office work and my attempts to brush these thoughts away as unworthy are rarely successful. Then, again, in the evenings I sometimes take my two dachshunds for a stroll. For a dog, going for a walk is the ultimate feelgood experience. Mention the word ‘walkies’ to a wiener dog, and he is immediately transported into new dimensions of bliss. I couldn’t produce a similar reaction in my wife if I proposed that we take the Concorde to Paris for the weekend. Rather than suffer a walk, my son would prefer to have his teeth drilled.

In no way am I suggesting that all of society’s ills can be cured by a renaissance of walking. But maybe – just maybe – a renewed interest in walking may spur some fresh scientific discoveries, a unique literary movement, a new vein of philosophy. If nothing else it will certainly improve our health both physically and mentally. Of course that would mean getting out from behind the desk at noon and getting some fresh air. That would mean shutting down the television in the evenings and breathing in the Great Outdoors. And, ultimately, it would involve a change in thinking and a shift in behavior, as opposed to a change of channels and a shift into third.

If there is one idea intellectuals can agree upon it is that the act of ambulation – or as we say in the midwest, walking – often serves as a catalyst to creative contemplation and thought. It is a belief as old as the dust that powders the Acropolis, and no less fine. Followers of the Greek Aristotle were known as peripatetics because they passed their days strolling and mind-wrestling through the groves of the Academe. The Romans’ equally high opinion of walking was summed up pithily in the Latin proverb: “It is solved by walking.” [solvitur ambulando]

Nearly every philosopher-poet worth his salt has voiced similar sentiments. Erasmus recommended a little walk before supper and “after supper do the same.” Thomas Hobbes had an inkwell built into his walking stick to more easily jot down his brainstorms during his rambles. Jean- Jacques Rousseau claimed he could only meditate when walking: “When I stop, I cease to think,” he said. “My mind only works with my legs.” Søren Kierkegaard believed he’d walked himself into his best thoughts. In his brief life Henry David Thoreau walked an estimated 250,000 miles, or ten times the circumference of earth. “I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits,” wrote Thoreau, “unless I spend four hours a day at least – and it is commonly more than that – sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields absolutely free from worldly engagements.” Thoreau’s landlord and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson characterized walking as “gymnastics for the mind.”

In order that he might remain one of the fittest, Charles Darwin planted a 1.5 acre strip of land with hazel, birch, privet, and dogwood, and ordered a wide gravel path built around the edge. Called Sand-walk, this became Darwin’s ‘thinking path’ where he roamed every morning and afternoon with his white fox-terrier. Of Bertrand Russell, long-time friend Miles Malleson has written: “Every morning Bertie would go for an hour’s walk by himself, composing and thinking out his work for that day. He would then come back and write for the rest of the morning, smoothly, easily and without a single correction.”

None of these laggards, however, could touch Friedrich Nietzsche, who held that “all truly great thoughts are conceived by walking.” Rising at dawn, Nietzsche would stalk through the countryside till 11 a.m. Then, after a short break, he would set out on a two-hour hike through the forest to Lake Sils. After lunch he was off again, parasol in hand, returning home at four or five o’clock, to commence the day’s writing.

Not surprisingly, the romantic poets were walkers extraordinaire. William Wordsworth traipsed fourteen or so miles a day through the Lake District, while Coleridge and Shelley were almost equally energetic. According to biographer Leslie Stephen, “The (English) literary movement at the end of the 18th century was…due in great part, if not mainly, to the renewed practice of walking.”

Armed with such insights, one must wonder whether the recent decline in walking hasn’t led to a corresponding decline in thinking. Walking, as both a mode of transportation and a recreational activity, began to fall off noticeably with the rise of the automobile, and took a major nosedive in the 1950s. Fifty plus years of automobile-centric design has reduced the number of sidewalks and pedestrian-friendly spaces to a bare minimum (particularly in the American west). All of the benefits of walking: contemplation, social intercourse, exercise, have been willingly exchanged for the dubious advantages of speed and convenience, although the automobile alone cannot be blamed for the maddening acceleration of everyday life. The modern condition is one of hurry, a perpetual rush hour that leaves little time for meditation. No wonder then that in her history of walking, Rebecca Solnit mused that “modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought, or thoughtfulness,” which seems the antithesis of Wittgenstein’s observation that in the race of philosophy, the prize goes to the slowest.

If we were to compare the quantity and quality of thinkers of the early 20th century with those of today, one cannot help but notice the dearth of Einsteins, William Jameses, Eliots and Pounds, Freuds, Jungs, Keynes, Picassos, Stravinskys, Wittgensteins, Sartres, Deweys, Yeats and Joyces.... Mark Twain... “walking is good to time the movement of the tongue by, and to keep the blood and the brain stirred up and active.” Others have concluded that walking’s two-point rhythm clears the mind for creative study and reflection... And while Einstein may have been a devoted pedestrian (daily hoofing the mile-and-a-half walk between his little frame house at 112 Mercer Street and his office at Princeton’s Fuld Hall), the inability to walk has not much cramped Stephen Hawking’s intellectual style. [But how would we know?!]

...Here, where the average citizen walks a measly 350 yards a day, it is not surprising that half the population is diagnosed as obese or overweight. Despite such obscene girth, I have sat through planning commission meetings and heard civil engineers complain that it would be a waste of money to lay down sidewalks since no one walks anyway. No one thought to ask if perhaps we do not walk because there are no sidewalks. Even today, the typical urban planner continues to regard the pedestrian as “the largest single obstacle to free traffic movement.”

To paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, walking remains for me the best “of all exercises.” Even so, I am full of excuses to stay put. My neighborhood has no sidewalks and it is downright dangerous to stroll the streets at night; if the threat does not come directly from thugs, then from drunken teens in speeding cars. There are certainly no Philosophers’ Walks in my hometown, as there are near the universities of Toronto, Heidelberg, and Kyoto. Nor are there any woods, forests, mountains or glens. “When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and the woods,” said Thoreau. “What would become of us, if we only walked in a garden or a mall?” I suppose I am what becomes of us, Henry.

At noon, if the weather cooperates, I may join a few other nameless office drudges on a stroll through the riverfront park. My noon walk is a brief burst of freedom in an otherwise long, dreary servitude. Though I try to reserve these solitary walks for philosophical ruminations, my subconscious doesn’t always cooperate. Often I find my thoughts to be pedestrian and worrisome in nature. I fret over money problems, or unfinished office work and my attempts to brush these thoughts away as unworthy are rarely successful. Then, again, in the evenings I sometimes take my two dachshunds for a stroll. For a dog, going for a walk is the ultimate feelgood experience. Mention the word ‘walkies’ to a wiener dog, and he is immediately transported into new dimensions of bliss. I couldn’t produce a similar reaction in my wife if I proposed that we take the Concorde to Paris for the weekend. Rather than suffer a walk, my son would prefer to have his teeth drilled.

In no way am I suggesting that all of society’s ills can be cured by a renaissance of walking. But maybe – just maybe – a renewed interest in walking may spur some fresh scientific discoveries, a unique literary movement, a new vein of philosophy. If nothing else it will certainly improve our health both physically and mentally. Of course that would mean getting out from behind the desk at noon and getting some fresh air. That would mean shutting down the television in the evenings and breathing in the Great Outdoors. And, ultimately, it would involve a change in thinking and a shift in behavior, as opposed to a change of channels and a shift into third.

© CHRISTOPHER ORLET 2004/ Philosophy Now

==

HEAVEN’S GAITSWhat we do when we walk. By Adam GopnikWhy people walk is a hard question that looks easy. Upright bipedalism seems such an obvious advantage from the viewpoint of those already upright that we rarely see its difficulty. In the famous diagram, Darwinian man unfolds himself from frightened crouch to strong surveyor of the ages, and it looks like a natural ascension: you start out bending over, knuckles dragging, timidly scouring the ground for grubs, then you slowly straighten up until there you are, staring at the skies and counting the stars and thinking up gods to rule them. But the advantages of walking have actually been tricky to calculate. One guess among the evolutionary biologists has been that a significant advantage may simply be that walking on two legs frees up your hands to throw rocks at what might become your food—or to throw rocks at other bipedal creatures who are throwing rocks at what might become their food. Although walking upright seems to have preceded throwing rocks, the rock throwing, the biologists point out, is rarer than the bipedalism alone, which we share with all the birds, including awkward penguins and ostriches, and with angry bears. Meanwhile, the certainty of human back pain, like the inevitability of labor pains, is evidence of the jury-rigged, best-solution-at-hand nature of evolution.

Over time, though, things we do for a purpose, however obscure in origin, become things we do for pleasure, particularly when we no longer have to do them. As we do them for pleasure, they get attached either to a philosophy or to the pursuit of some profit. Two new accounts of this process have recently appeared, and although they occasionally make you want to throw things, they both illuminate what it means to be a pedestrian in the modern world.

Matthew Algeo’s “Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport” (Chicago Review) is one of those books which open up a forgotten world so fully that at first the reader wonders, just a little, if his leg is being pulled. How could there be an account this elaborate—illustrated with sober handbills, blaring headlines, starchy portrait photographs, and racy newspaper cartoons—of an enthusiasm this unknown? But it all happened. For several decades in the later nineteenth century, the favorite spectator sport in America was watching people walk in circles inside big buildings... (continues)

WHY WALKING HELPS US THINK. By Ferris Jabr

In Vogue’s 1969 Christmas issue, Vladimir Nabokov offered some advice for teaching James Joyce’s “Ulysses”: “Instead of perpetuating the pretentious nonsense of Homeric, chromatic, and visceral chapter headings, instructors should prepare maps of Dublin with Bloom’s and Stephen’s intertwining itineraries clearly traced.” He drew a charming one himself. Several decades later, a Boston College English professor named Joseph Nugent and his colleagues put together an annotated Google map that shadows Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom step by step. The Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain, as well as students at the Georgia Institute of Technology, have similarly reconstructed the paths of the London amblers in “Mrs. Dalloway.”

Such maps clarify how much these novels depend on a curious link between mind and feet. Joyce and Woolf were writers who transformed the quicksilver of consciousness into paper and ink. To accomplish this, they sent characters on walks about town. As Mrs. Dalloway walks, she does not merely perceive the city around her. Rather, she dips in and out of her past, remolding London into a highly textured mental landscape, “making it up, building it round one, tumbling it, creating it every moment afresh.”

Since at least the time of peripatetic Greek philosophers, many other writers have discovered a deep, intuitive connection between walking, thinking, and writing. (In fact, Adam Gopnik wrote about walking in The New Yorker just two weeks ago.) “How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live!” Henry David Thoreau penned in his journal. “Methinks that the moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow.” Thomas DeQuincey has calculated that William Wordsworth—whose poetry is filled with tramps up mountains, through forests, and along public roads—walked as many as a hundred and eighty thousand miles in his lifetime, which comes to an average of six and a half miles a day starting from age five.

What is it about walking, in particular, that makes it so amenable to thinking and writing? The answer begins with changes to our chemistry. When we go for a walk, the heart pumps faster, circulating more blood and oxygen not just to the muscles but to all the organs—including the brain. Many experiments have shown that after or during exercise, even very mild exertion, people perform better on tests of memory and attention. Walking on a regular basis also promotes new connections between brain cells, staves off the usual withering of brain tissue that comes with age, increases the volume of the hippocampus (a brain region crucial for memory), and elevates levels of molecules that both stimulate the growth of new neurons and transmit messages between them... (continues)

==

An old post-

Friday, July 10, 2015

Whitman and Proust

6:30/5:39, 72/95. Podcast

Birthday of Calvin and Proust. Two more disparate human types would be hard to yoke. One championing our Total Depravity, claiming infants enter the world already damned; the other luxuriating in the sensual subjective experience of memory and longing. I have no use at all for the TULIP-planter. But Proust, despite our popular image of him tucked away writing in his cork-lined chamber, was actually a peripatetic. There are passages in Memory of Things Past that illustrate the accuracy of a quote the brainpicker featured yesterday:

Friday, July 10, 2015

Whitman and Proust

6:30/5:39, 72/95. Podcast

Birthday of Calvin and Proust. Two more disparate human types would be hard to yoke. One championing our Total Depravity, claiming infants enter the world already damned; the other luxuriating in the sensual subjective experience of memory and longing. I have no use at all for the TULIP-planter. But Proust, despite our popular image of him tucked away writing in his cork-lined chamber, was actually a peripatetic. There are passages in Memory of Things Past that illustrate the accuracy of a quote the brainpicker featured yesterday:

Walking at our own pace creates an unadulterated feedback loop between the rhythm of our bodies and our mental state that we cannot experience as easily when we’re jogging at the gym, steering a car, biking, or during any other kind of locomotion. When we stroll, the pace of our feet naturally vacillates with our moods and the cadence of our inner speech; at the same time, we can actively change the pace of our thoughts by deliberately walking more briskly or by slowing down.

Because we don’t have to devote much conscious effort to the act of walking, our attention is free to wander—to overlay the world before us with a parade of images from the mind’s theatre. This is precisely the kind of mental state that studies have linked to innovative ideas and strokes of insight...

Perhaps the most profound relationship between walking, thinking, and writing reveals itself at the end of a stroll, back at the desk. There, it becomes apparent that writing and walking are extremely similar feats, equal parts physical and mental. When we choose a path through a city or forest, our brain must survey the surrounding environment, construct a mental map of the world, settle on a way forward, and translate that plan into a series of footsteps. Likewise, writing forces the brain to review its own landscape, plot a course through that mental terrain, and transcribe the resulting trail of thoughts by guiding the hands. Walking organizes the world around us; writing organizes our thoughts. How walking helps us think.

That was in the New Yorker last September, as was an insightful Adam Gopnik essay/review[correction: earlier & in the podcast I confused Gopnik with Remnick... can't tell your New Yorker players without a scorecard] of the more recent and self-appointed French philosopher of walking I've been ridiculing, Frederic Gros. It didn't change my mind about Professor Gros being an unfortunate and misleading spokesman for my favorite non-spectatorial pastime. Gopnik draws the correct contrast between walking as an escape into solitude, away from a robust sense of self, versus walking as connection, walking as much toward an identity as away. Walt Whitman is the paradigmatic exemplar of the latter. I'm wondering if Gros's sensibility, in this regard, is more Proustian. Or is Proust's more Whitmanesque? And how do they all relate to the first French philosopher of walking, Michel de Montaigne, who said "my thoughts sleep if I sit still"?

==

From 7.8.15-

French philosopher Frederic Gros's bestselling (in France, of course) A Philosophy of Walking struck one reviewer as missing the distaff half. Gros's subjects are "various thinkers for whom walking was central to their work –Nietzsche, Rimbaud,Kant, Rousseau, Thoreau (they're all men; it's unclear if women don't walk or don't think)..." Well, women have always walked and thought. Dorothy Wordsworth and Jane Austen spring instantly to mind, among Brits. Over here, Margaret Fuller probably walked with Emerson and Thoreau. More recently, Annie Dillard, Rebecca Solnit, Cheryl Strayed... Put this on your research list, S: find us some more walking/writing/thinking women.

I've resisted reading Gros, fearing to discover that he'd scooped me and my dilatory Philosophy Walks project. But if this passage and the reviewer's response is any indication, Gros's take on the subject is not at all like mine.

Poor Professor Gros "started to look depressed. So, you don't manage to walk much on a day-to-day basis?" What? The philosopher of walking is sedentary?! He definitely should get a dog.

Looks like I'm going to have to write my book. Monsieur Gros has not written it.

==

From 7.8.15-

French philosopher Frederic Gros's bestselling (in France, of course) A Philosophy of Walking struck one reviewer as missing the distaff half. Gros's subjects are "various thinkers for whom walking was central to their work –Nietzsche, Rimbaud,Kant, Rousseau, Thoreau (they're all men; it's unclear if women don't walk or don't think)..." Well, women have always walked and thought. Dorothy Wordsworth and Jane Austen spring instantly to mind, among Brits. Over here, Margaret Fuller probably walked with Emerson and Thoreau. More recently, Annie Dillard, Rebecca Solnit, Cheryl Strayed... Put this on your research list, S: find us some more walking/writing/thinking women.

I've resisted reading Gros, fearing to discover that he'd scooped me and my dilatory Philosophy Walks project. But if this passage and the reviewer's response is any indication, Gros's take on the subject is not at all like mine.

Rousseau says in his Confessions, when you walk all is possible. Your future is as open as the sky in front of you. And if you walk several hours, you can escape your identity. There is a moment when you walk several hours that you are only a body walking. Only that. You are nobody. You have no history. You have no identity. You have no past. You have no future. You are only a body walking.I've walked a lot over the decades, but I've never walked entirely away from my identity and my history. Or ours. I've never been only a body walking, or an Emersonian "transparent eyeball" either.

Poor Professor Gros "started to look depressed. So, you don't manage to walk much on a day-to-day basis?" What? The philosopher of walking is sedentary?! He definitely should get a dog.

Looks like I'm going to have to write my book. Monsieur Gros has not written it.

==

7.15.15

Deconstruct this post

I tweeted earlier that the real world awaits our discovery, but should of course have pluralized the statement: there are realities and worlds, new horizons (not just Pluto's) to scope out, implying or at least intending a critique of deconstructionist heavy textuality.

I don't have the time or the patience to work that up, and there doubtless are moves the other side in the postmod-decon language game would make if I did. I'm no expert on that. The whole discussion/debate feels so 'eighties, so Grad School. (I do see the Rorty Society's new call for papers has been issued.)

But the point I want to punch right now, the textual proposition I want to punctuate, is simply that when I go walking, pedaling, and swimming (okay, floating mostly) each morning I'm also looking for real worlds and new horizons. Or refreshed and renewed horizons, minimally. The fact that I almost always entertain some problematic discursive query or concern while in motion, for a fraction of that time anyway, does not alter the fact that a key element of the total experience feels light and non-discursive, in a very good way.

So, my philosophy of walking denies the dichotomy between working and recreating, the dualism of discoursing and experiencing that I think I read in Frederic Gros. I need now to go back and re-read his Thoreau section, with the question before me: does he also take from Henry what I do, viz., a sense of walking as a form of life that straddles the worlds of text and experience? Again, I must pluralize. Texts, experiences, realities are my quarry, not just words and verbal constructs. Something there is, Horatio (and Jacques), that is not merely dreamed up and written in your philosophy texts. That's one of the implications of "more day to dawn."

If I'm right, I must of course use words and texts to tell you about it. That's where this language game gets so tricky, and it's why I'm always wondering about the pre- and post-poetic experience of poets. A poet is, ex hypothesi, a textualizer who draws from a well deeper than words. We all do that, good poets just do it with greater sub-surface dexterity.

If these words mean anything, they mean something real. If real means anything, it means something extra-verbal. That I must use words to point that out and you must use them to take my point may be funny and ironic, but it's not deconstructive. Is it?

I tweeted earlier that the real world awaits our discovery, but should of course have pluralized the statement: there are realities and worlds, new horizons (not just Pluto's) to scope out, implying or at least intending a critique of deconstructionist heavy textuality.

I don't have the time or the patience to work that up, and there doubtless are moves the other side in the postmod-decon language game would make if I did. I'm no expert on that. The whole discussion/debate feels so 'eighties, so Grad School. (I do see the Rorty Society's new call for papers has been issued.)

But the point I want to punch right now, the textual proposition I want to punctuate, is simply that when I go walking, pedaling, and swimming (okay, floating mostly) each morning I'm also looking for real worlds and new horizons. Or refreshed and renewed horizons, minimally. The fact that I almost always entertain some problematic discursive query or concern while in motion, for a fraction of that time anyway, does not alter the fact that a key element of the total experience feels light and non-discursive, in a very good way.

So, my philosophy of walking denies the dichotomy between working and recreating, the dualism of discoursing and experiencing that I think I read in Frederic Gros. I need now to go back and re-read his Thoreau section, with the question before me: does he also take from Henry what I do, viz., a sense of walking as a form of life that straddles the worlds of text and experience? Again, I must pluralize. Texts, experiences, realities are my quarry, not just words and verbal constructs. Something there is, Horatio (and Jacques), that is not merely dreamed up and written in your philosophy texts. That's one of the implications of "more day to dawn."

If I'm right, I must of course use words and texts to tell you about it. That's where this language game gets so tricky, and it's why I'm always wondering about the pre- and post-poetic experience of poets. A poet is, ex hypothesi, a textualizer who draws from a well deeper than words. We all do that, good poets just do it with greater sub-surface dexterity.

If these words mean anything, they mean something real. If real means anything, it means something extra-verbal. That I must use words to point that out and you must use them to take my point may be funny and ironic, but it's not deconstructive. Is it?

==

7.20.15

We crave only reality

I may have been hasty in detecting deconstructionist tendencies in Frederic Gros's Philosophy of Walking. Overtly at least, he's on the side of immediate experience and reality, against that of the Derridean overtextualizers. Or so it appears, given his sympathetic rendition of Thoreau's famous "rocks in place" declaration of independence from tradition, convention, and cultural inertia. Honest writing must first acknowledge the truth of the writer's own experience. If he cannot tap that well, he has no business writing. "How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live."

Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion, and appearance, that alluvion which covers the globe, through Paris and London, through New York and Boston and Concord, through Church and State, through poetry and philosophy and religion, till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we can call reality, and say, This is, and no mistake; and then begin, having a point d'appui, below freshet and frost and fire, a place where you might found a wall or a state, or set a lamp-post safely, or perhaps a gauge, not a Nilometer, but a Realometer, that future ages might know how deep a freshet of shams and appearances had gathered from time to time. If you stand right fronting and face to face to a fact, you will see the sun glimmer on both its surfaces, as if it were a cimeter, and feel its sweet edge dividing you through the heart and marrow, and so you will happily conclude your mortal career. Be it life or death, we crave only reality. If we are really dying, let us hear the rattle in our throats and feel cold in the extremities; if we are alive, let us go about our business. Walden, "Where I Lived and What I Lived For"

"What do you mean, we?" asks (implicitly) Andrew O'Hagan in his unexpectedly fine essay in yesterday's Times style magazine. "The Happiness Project" tries to see the world of Disney through his children's eyes, as well as his own. The reality of that fantasy is something to be experienced, too, and "the greatest ride in Disneyland is the ride through one's own ambivalence... In Disneyland, every child feels chosen, and why wouldn't you empty your bank account to see that happen, when the child is yours... only a curmudgeon, or a writer, would choose to question the authenticity of the performers' smiles or ask how much they are being paid."So maybe I was a little hard on Goofy the other day too. Just trying to keep it real.

“You will never be happy if you continue to search for what happiness consists of. You will never live if you are looking for the meaning of life.”

ReplyDelete― Albert Camus

“Life has no meaning. Each of us has meaning and we bring it to life. It is a waste to be asking the question when you are the answer.”

― Joseph Campbell

A life that partakes even a little of friendship, love, irony, humor, parenthood, literature, and music, and the chance to take part in battles for the liberation of others cannot be called 'meaningless' except if the person living it is also an existentialist and elects to call it so. It could be that all existence is a pointless joke, but it is not in fact possible to live one's everyday life as if this were so. Whereas if one sought to define meaninglessness and futility, the idea that a human life should be expended in the guilty, fearful, self-obsessed propitiation of supernatural nonentities…”

― Christopher Hitchens

Extra Credit Discussion:

ReplyDeleteWould you allow or regulate genetic engineering intended to make people happier?

I don’t believe I would allow such a potentially insalubrious practice to happen. Albeit, if it did -which is a serious possibility, (given our advances in technology and knowledge concerning genetics) regardless of what I, or others think of the matter and its’ possible implications - I wouldn’t mind to, at the very least, regulate or closely monitor this presumably, damningly, homogenizing concept of designer, emotional engineering . (withal, to be perfectly honest, I am under the assumption that it is unlikely that I would/could be allotted such a position/ability to actually regulate or approve/disapprove this contentious and increasingly introspective topic; due to my own lack of province concerning this faction of science–and what could be an unfair bias, because I am not genetically pre-dispositioned to chronic depression/unhappiness.in addition, my, possibly, rash, purely, philosophically based, purporting on this subject could be perceived as unethical or marginalizing those who support the use of designer-possibly, cosmetic in some regards- artificial improvement” of our happiness. Nonetheless, I still would, and will, fervently opposed the usage of unnatural/ genetically invasive improvements to the happiness of others; although, I will not judge, at least, too harshly, those who support or attempt to improve their own – I believe that children/embryos should be allotted the privilege to decide on their own tot themselves- be rtificially/by genetically invasive means

With that being said, I find that question of when, as well as, the ethical, philosophical and psychological implications of this liaison with an “absolute and perfect happiness” to be more tendentious and peculiar, rather than what my views on the matter are; especially, given that my views are probably moot and insignificant in the ears of the government and/or those that will be and are financially and ardently backing this ensuing adaption to imperfection. I mean, it is only eventual after all that this surgery will become a seriously possibility to the public.

On another, similar, note, it is also only eventual that there will be something/someone that will surpass what we currently consider/know to be human. Whether it be a quasi-Frankenstein of our own design –personally, I believe sentient robots or these genetically “perfect and happy beings” akin to humans, are our most plausible unintentional heir- or another species entirely, we are bound to be replaced eventually. As for the relevant, and most likely successor, to our reign, the genetically modified, “perfectly happy human”, I find that I am not stepping too far out of the realm of sanity and possibility to equate that our relationship –given that this practice is put into production- could be seen as/would be much like that of that of the single celled organisms that existed only to produce multi-cellular organisms.

Moreover, I believe that this, potential, experimentation and implementation of genetic improvement to become happier -or even ethereal to some, due to the likelihood that our egos will begin run wild from “playing god”- would ruin the very definition and existence of what of genuine and real happiness.; it would be easy to predict and perceive our species becoming less human, in a senses, in due time. I believe that our other affects are what help us define our happiness, as well as, granting us a, somewhat, accurate scale, or frame of reference, with which to understand and experience happiness; although, according to many researchers, we are terrible judges of our own emotional state. Overall, from my perspective, happiness is not something that one can or should produce artificially and strongly advise against, else, we will run the risk of losing many of the identifiers that characterize us as human, and possibly happiness altogether, form this potentially damning and controversial domino.

1. Is anything worse, in your experience, than futile, hopeless labor?

ReplyDeleteWell, I can't say that I've experienced futile hopeless labor before, so I'm not 100% sure. However, I'm sure a life full of constant, never ending pain and suffering (say, not being able to die of thirst while being surrounded by pools of fresh water that you cannot physically drink out of) could potentially be worse since there's the pain factor that comes into play.

2. What could it mean for a mortal to put Death in chains?

To conquer death, I think. Find the means to be truly immortal. This was such a bad thing because in our reality, throughout the cosmos, everything dies one way or another and comes to an end so that birth may happen elsewhere from the same material.

3. Must we imagine Sisyphus happy?

No. He could be stubborn and unhappy as well. But the purpose of the story is so that we can picture Sisyphus unhappy. Its purpose is to picture an extreme situation and to see whether or not we can find a way to be happy in said situation.

Do you find that a long walk (hike, bikeride, or some other personally-functional equivalent) makes you feel more yourself, or less like a self at all?

ReplyDeleteI definitely feel like a long hike grounds me to who I am, my reality, and helps me come to terms with the current situation and current stage of progression through life. Sometimes that means becoming more in tune with myself, and sometimes that means losing myself a bit and reconnected with nature and having a sense of universal oneness. It just kind of depends I think, if that's an option.

Possible Quiz Questions (Nov. 2) Phil of Walking

ReplyDelete1. What are various characteristics of a sport?

2. What does a man (or person, perhaps) do once they are on their feet?

3. What three things compose freedom, according to the author?

4. What alienates you from speed?

5. What poet has Kerouac been reading?

6. What excesses can walking provoke?

7. What are your commitments in Hell, considered by the author?

8. Who are some of the Greek authors Nietzsche reads as a philology professor?

9. Thinking outdoors is a habit that functions with the activities of what, according to Nietzsche?

10. How do you judge the quality of a piece of music?

Possible Discussion Questions:

1. Do you ever participate in long walks, like Nietzsche, over six hours or more? Why or why not?

2. Why do you think Nietzsche stated that the quality of a book is based on its ability to dance? What do you think he meant by that statement?

3. Have you ever been able to experience an "Ah ha!" moment while participating in a long walk? Why do you think you where or where not able to?